The Psychology of Spatial Proxemics

Abstract

Spatial proxemics is the study of how people use personal space. It was first conceptualized by anthropologist Edward T. Hall. Hall defined proxemics as “the interrelated observations and theories of man’s use of space as a specialized elaboration of culture”. This interdisciplinary field examines the psychological mechanisms by which individuals regulate distance in social interactions and how these norms vary culturally. Proxemic distances all, intimate, personal, social, public, have been quantified e.g. Hall’s zones range roughly from 0–0.46m for intimate to >3.7m for public. Contemporary research links these spatial behaviors to neural circuitry like, amygdala responses to personal distance, emotional states like social anxiety drives greater distance, and life-span development like preferred distances shrink with age. Cultural comparisons (Sorokowska et al., 2017) reveal wide variation: for example, women and older individuals tend to maintain larger interpersonal distances, with climate also a factor. This review integrates foundational theory and recent empirical findings on proxemics, including its impact on communication, social behavior, and mental health. We examine applications in real-world settings – workplaces, classrooms, healthcare, and urban design – and discuss emerging areas such as social robotics and virtual reality. Finally, we address implications for policy and design, emphasizing how insights from proxemic psychology can guide the creation of more effective, human-centered environments and technologies.

Introduction

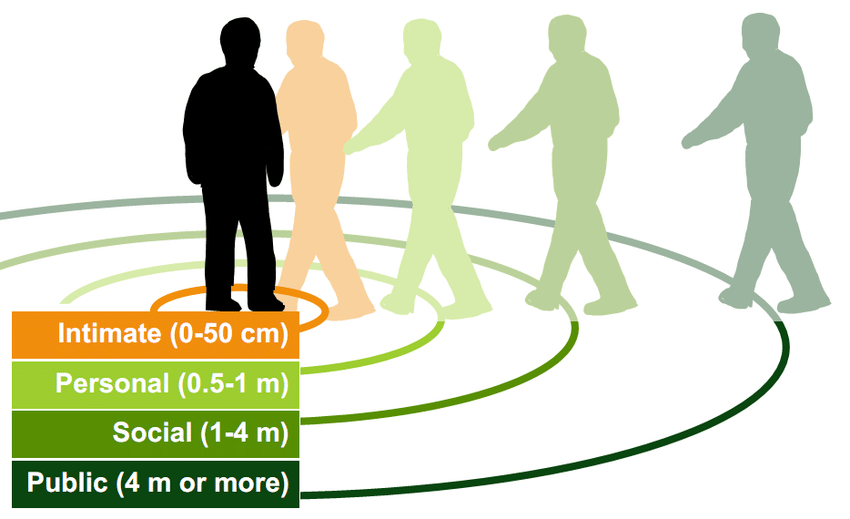

Human beings unconsciously regulate the space around their bodies in social contexts, maintaining “personal bubbles” of varying size depending on the situation and the other person. Edward T. Hall (1966) introduced the concept of proxemics, observing that each culture embeds tacit rules about personal distance: people from the same background often share similar comfort zones, whereas outsiders might find those norms either intrusive or standoffish. For example, Hall’s classic zone model delineates intimate, personal, social, and public distances.

|

Hall's proxemic zones.

Edward T. Hall

Proxemics originated in anthropology and communication studies. Hall’s Hidden Dimension (1966) argued that space functions like a silent language: we “speak” with the distance we keep from others, often without realizing it. He identified four proxemic zones (intimate, personal, social, public) that apply across many cultures, though the exact measurements differ (for instance, Latin American cultures often tolerate closer distances than Northern Europeans). Contemporary sources also cite Argyle and Dean’s work, noting that eye contact and movement modulate these zones. Proxemics bridges anthropology and psychology by linking these spatial patterns to cognitive and emotional processes.

Neurologically, personal-space regulation is tied to brain systems for threat and reward. In a seminal study, Kennedy et al. (2009) reported that a patient with bilateral amygdala damage showed no personal-space barrier: she permitted others to come unusually close and felt no discomfort. Conversely, fMRI in healthy individuals revealed that the amygdala activates when a stranger enters one’s proxemic zone. These findings suggest the amygdala triggers the “emotional reaction” when personal space is violated. Other neuroscientists describe this as a peripersonal defensive space, where nearby stimuli elicit heightened arousal or avoidance responses.

In one study, Tootell et al. (2021) measured discomfort ratings and physiological arousal as people (and virtual avatars) approached participants in VR. They found that discomfort increases nonlinearly at close range (following a power-law function). They propose the brain computes personal-space boundaries in a coarse “rough sketch” stage that generalizes across human and human-like stimuli. This implies that our sense of personal space is an innate perceptual system linking vision, emotion, and bodily states.

Psychologically, individual differences matter. Attachment style, anxiety, and social experience influence preferred distances. Mirlisenna et al. (2024) examined children through older adults (3–89 years old) and confirmed that interpersonal distance declines with age: children keep more distance from strangers and even familiar others than teenagers or adults do.

Moreover, people with social anxiety reliably choose larger distances to avoid discomfort. Those with autism spectrum features may show atypical proxemics, though studies are mixed (some suggest inconsistent spatial preferences in ASD). In social phobia, by contrast, the pattern is clear: anxious individuals maintain extra space, likely as a safety buffer during interactions. These findings link proxemics to broader models of emotion regulation and social cognition: distance can be used (consciously or not) to manage arousal and uncertainty.

Cultural and Contextual Variations

Proxemic norms vary dramatically across cultures and contexts. Large-scale surveys (Sorokowska et al., 2017) have measured “preferred interpersonal distance” in hundreds of countries. In one global study of 8,943 participants from 42 nations, researchers found significant cross-cultural differences in all distance zones. For example, people from colder climates (e.g. Northern Europe) tend to prefer greater distance from strangers than do people in warmer regions. Women and older individuals also reported larger comfort distances, especially in interactions with acquaintances or strangers. Within cultures, gender norms often dictate spacing: some studies show that during conversation, females may stand closer than males in casual settings. Context also matters: people give more space in formal or hierarchic settings (e.g. speaking to a superior) and less in casual gatherings.

Historical and situational factors shape proxemic behavior as well. The advent of crowded urban living and mass transportation has increased exposure to strangers, possibly shifting tolerances for proximity. Recent events like the COVID-19 pandemic had a pronounced effect on public proxemics: enforced social distancing made people acutely aware of safe distances, a change noted by urban designers and planners. Thus, even fixed cultural norms can evolve with experience and environmental pressures. In sum, culture provides the baseline rules of proxemic etiquette, but these are always modulated by immediate context (work vs. family), relative power, and temporary conditions (e.g. crowding or health guidelines).

Proxemics in Interpersonal Communication and Social Behavior

Proxemic behavior is a cornerstone of nonverbal communication. Distance conveys intimacy, dominance, or formality: stepping back signals discomfort or deference, while stepping closer can show affection or assertiveness. In groups, people form “F-formations” (facing circles or triangles) that facilitate eye contact and conversation. Proxemics also ties into other channels: when eye contact is limited, people often compensate with closer proximity, and vice versa. Aberrant proxemic behavior can thus disrupt communication.

In social psychology experiments, violations of expected personal space often cause discomfort or anger. For example, if a stranger stands too close in conversation, listeners rate the interaction negatively. Conversely, allies or friends standing closer can enhance rapport. These effects have been documented in many real-world settings.

In workplaces, respecting personal distance can reduce stress and misunderstandings (whereas open-plan offices are often criticized for eroding privacy). In education, teachers who use space to approach students – walking around the classroom or sitting nearby – are seen as more engaging. For instance, Buai Chin et al. (2017) found that Chinese language students “enjoyed having close interaction with their teachers,” and that this sense of closeness enhanced learning. Thus instructional proxemics (the teacher’s use of physical space) is an important but underappreciated factor in pedagogy.

Healthcare interactions also hinge on proxemics. Nurses and doctors adjust distance to convey empathy or maintain professionalism. A grounded-theory study of nurse–patient communication identified proxemics as one of four key nonverbal channels. Nurses reported that sitting close to an older patient (even on their bed) can build rapport, whereas staying at the door or turning away can signal detachment. These findings underscore that spatial distance is part of the “bedside manner” – medical professionals learn culturally appropriate distances for greeting, examination, and comforting. In crowded emergency rooms or on pandemic wards, however, personal space is often compromised, which can increase patient anxiety. Overall, how space is used in social settings has measurable effects on communication efficiency and emotional outcomes.

Proxemics and Mental Health

Beyond social anxiety, proxemics has links to mental health. Comfortable personal space is associated with a sense of security and control. Chronic lack of personal space (as in extreme crowding or intrusive environments) can contribute to stress and aggression over time. Conversely, enforced distancing (such as during lockdowns) can intensify feelings of isolation. Some researchers have argued that disorders like agoraphobia or claustrophobia can be conceptualized as extreme disruptions of proxemic regulation – either an inability to tolerate crowded spaces or difficulty venturing out of one’s comfort zone. Quantitative evidence is limited, but there is clinical interest in using proxemic awareness as part of therapy. For example, virtual reality (VR) exposure can safely simulate personal-space intrusions to treat social anxiety. VR studies show that close encounters with virtual humans elicit similar discomfort as with real people. Kroczek et al. (2020) demonstrated that VR simulations of approaching avatars produced higher arousal and lower pleasantness at close distances, especially for socially anxious individuals. Such work suggests that proxemic VR may become a tool for training and desensitization in clinical contexts.

This paper is a narrative review of spatial proxemics, synthesizing findings from anthropology, psychology, neuroscience, and applied studies. We conducted comprehensive literature searches in academic databases (e.g. PubMed, PsycINFO, Google Scholar) for terms related to proxemics, personal space, and interpersonal distance. Both classic sources (e.g. Hall’s foundational texts) and recent empirical research were included. Peer-reviewed journal articles, books, and academic theses were examined for relevant data on proxemics theory, mechanisms, cross-cultural studies, and applications. Relevant case studies (workplace design, education, healthcare) were drawn from practice-oriented reports and dissertations. Given the interdisciplinary nature of proxemics, we prioritized sources that explicitly link spatial behavior to psychological or social outcomes. Limitations of this review include potential publication bias toward studies from Western and East Asian contexts; we attempted to include broader surveys (e.g. Sorokowska et al., 2017) to mitigate this.

Spatial Proxemics in Applied Settings

Workplace: Personal space in the workplace affects satisfaction and productivity. Open-plan offices, though intended to foster collaboration, often violate proxemic comfort. Employees in such settings report reduced privacy and increased distraction (Gan, 2019). Gan’s study of Silicon Valley startups notes that “rows of tables” with minimal separation give “zero consideration” to personal space, despite evidence that employees work better when given privacy. Companies designing offices now pay attention to proxemic needs by providing quiet zones, adjustable partitions, and flexible workstations. Addressing proxemic norms can improve morale: for example, allowing workers to adjust desk layouts or sit where they feel comfortable respects diverse spatial preferences.

Education: Classroom layout is another domain of proxemic impact. Rows of desks versus circular seating create different spatial climates. Buai Chin et al. found that student learning increased when teachers used instructional proxemics – moving around the room and sitting near students at times. In contrast, teachers who remain fixed or distant may seem less engaging. School architects and educators can apply these insights: designs with movable furniture and spaces for small-group interaction (rather than rigid front-facing layouts) can facilitate optimal proxemic distances. Training programs for teachers may even incorporate proxemic awareness as part of “teacher immediacy” behaviors (e.g., standing close to a struggling student to offer help).

Healthcare: As noted, proximity in healthcare is sensitive. Clinics and hospital rooms are often deliberately designed with adequate spacing: for example, seating in waiting rooms is spaced to allow privacy while still enabling contact. In elder care, practitioners are taught to respect the patient’s territoriality (e.g. knock before entering, maintain an appropriate distance during routine care). Spatial considerations also appear in mental health: therapy offices often use chairs placed at some distance (not touching) to balance intimacy and professional boundaries. On the policy level, healthcare guidelines (especially post-COVID) have enforced minimum distances in public health contexts, illustrating how proxemic research can inform practical rules.

Urban and Public Spaces: City planners consider proxemics when designing parks, plazas, and transit areas. A well-designed public space provides both communal areas and semi-private niches. After the COVID-19 pandemic, experts emphasized the need for social distancing and inclusive design. For example, adding more benches and widening sidewalks can accommodate people who naturally keep larger distances. Mixed-use developments often include “third places” (cafés, alcoves) where people can self-organize into comfortable personal-space arrangements. The American Planning Association highlights that public spaces should make users feel “supported and welcome” – including allowing for a range of interpersonal distances. In transportation, proxemic principles guide how seats are arranged (e.g. staggered metro seats, barrier panels) to minimize crowding stress.

Cultural Proxemics in a Globalized World

Intercultural contact raises proxemic challenges. Migrants or global businesspeople often undergo a learning period to adapt to local space norms. Awareness programs (e.g. for expatriates) include proxemic differences as key cultural knowledge. For example, North Americans must learn that in many Middle Eastern or Latin American cultures, people stand much closer during conversation than they are used to. Organizations that operate globally (diplomats, international corps) may use proxies like intercultural workshops to teach proxemic etiquette. In international healthcare or education, professionals are trained to ask permission before engaging in physical space (e.g. “May I sit here?”) when in doubt about local norms.

Social Robotics: As robots enter human environments, they must respect human proxemics to seem natural. Recent reviews emphasize human–robot proxemics (HRP) as a design parameter. For example, service robots (e.g. in hotels or hospitals) are programmed to slow their approach and maintain a polite distance, mimicking human norms. Samarakoon et al. (2022) note that context-aware navigation requires the robot to gauge whether to stay farther (in open space) or closer (if the human is working at a desk). Studies have found that robot facial expressions and sounds influence preferred distance: humans keep more space if the robot looks angry, less if it is friendly. Personality also plays a role: shy or neurotic users prefer larger robot distances. These findings inform robotics designers to customize proxemic behavior – for instance, programming a robot to detect user comfort via sensors and adapt its path.

Virtual Reality and Telepresence: In VR environments, proxemics can be manipulated for therapy or social training. Virtual meetings often lack the usual distance cues, but VR can recreate them precisely. The VR proxemics research (Kroczek et al., 2020; Tootell et al., 2021) shows that even avatars elicit personal-space reactions similar to real humans. Designers of virtual classrooms or remote collaboration tools must consider virtual personal space – for example, how close virtual avatars should stand without causing discomfort. Some VR platforms now allow users to set personal-space “bubbles” to avoid the uncanny feeling of avatars invading their space. More broadly, proxemic principles are being built into human–machine interfaces: augmented reality systems may automatically resize remote user representations to maintain comfort. Research continues into “proxemic VR therapy” for autism or social anxiety, using controlled personal-space challenges.

Urban Technology and Policy: On a policy level, understanding proxemics can guide public health and architecture. Regulations on building occupancy (e.g. fire codes) implicitly rely on human spacing norms. COVID-19 showed how guidelines (keep 1.5–2m apart) are simplified versions of proxemic science. Future pandemic policies may refine distancing rules based on such research. In workplace policy, companies may set minimum space per employee or reconfigure layouts to allow flex-spacing. Educational and healthcare guidelines may specify spatial arrangements for infection control that also respect psychological comfort (e.g. transparent partitions that allow intimacy while providing separation). In sum, proxemic research provides evidence for “best practices” in space planning across domains.

Conclusion

Spatial proxemics lies at the intersection of psychology, anthropology, neuroscience, and design. Its foundational insight – that distance is a nonverbal form of communication – remains as relevant today as in Hall’s era, but now enriched by empirical science. Research has shown that proxemic preferences arise from brain mechanisms (amygdala, autonomic arousal), developmental trajectory, and social factors like anxiety. Cultural comparisons reveal both universal trends (e.g. comfort zones exist in all societies) and local variations (warmer climates, genders, and ages systematically differ in spacing). Crucially, spatial behavior is not merely academic: it affects real outcomes in communication, well-being, and performance.

Modern applications – from flexible office design to social robots – increasingly incorporate proxemic principles. Designers of environments and technologies benefit by “building in” space for personal comfort. For instance, robot developers can program more human-like approach behaviors, and educators can arrange classrooms to foster engagement. Policymakers, too, can use proxemic insights: clear distancing guidelines and space standards can improve public health and social harmony.

As society faces new challenges (global - virtual coexistence, aging populations), the study of proxemics is advancing. Cutting-edge tools like VR allow controlled manipulation of personal space, and cross-cultural experiments continue to map the diversity of human spacing rules. Future research may explore proxemics in cyberspace (how personal-space norms transfer online) and develop personalized environments that adapt to individuals’ comfort zones. In all, proxemics remains a vital lens for understanding the silent language of space and designing more empathetic human environments.

References

- Buai Chin, H. B., Cheong, C. Y. M., & Taib, F. (2017). Instructional proxemics and its impact on classroom teaching and learning. International Journal of Modern Languages and Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 69–84.

- Gan, K. (2019). Personal space and privacy in open offices (Unpublished master’s thesis). Iowa State University.

- Hall, E. T. (1966). The hidden dimension. Doubleday.

- Kennedy, D. P., Gläscher, J., Tyszka, J. M., & Adolphs, R. (2009). Personal space regulation by the human amygdala. Nature Neuroscience, 12(10), 1226–1227. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2381

- Kroczek, L. O. H., Pfaller, M., Lange, B., Müller, M., & Mühlberger, A. (2020). Interpersonal distance during real-time social interaction: Insights from subjective experience, behavior, and physiology. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 561. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00561

- Mirlisenna, I., Bonino, G., Mazza, A., Capiotto, F., Cappi, G. R., Cariola, M., … & Dal Monte, O. (2024). How interpersonal distance varies throughout the lifespan. Scientific Reports, 14, 25439. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74532-z

- Samarakoon, S. M. B. P., Muthugala, M. A. V. J., & Jayasekara, A. G. B. P. (2022). A review on human–robot proxemics. Electronics, 11(16), 2490. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11162490

- Sorokowska, A., Sorokowski, P., Hilpert, P., Cantarero, K., Frackowiak, T., Ahmadi, K., … Pierce, J. D. Jr. (2017). Preferred interpersonal distances: A global comparison. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(4), 577–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117698039.

- Tootell, R. B., Zapetis, S. L., Babadi, B., Nasiriavanaki, Z., Sudakov, P. D., Krekelberg, B., … Holt, D. D. (2021). Psychological and physiological evidence for an initial ‘rough sketch’ calculation of personal space. Scientific Reports, 11, 21033. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-99578-1

- Wanko Keutchafo, E. L., Kerr, J., & Baloyi, O. B. (2022). A model for effective nonverbal communication between nurses and older patients: A grounded theory inquiry. Healthcare, 10(11), 2119. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112119

Comments

Post a Comment